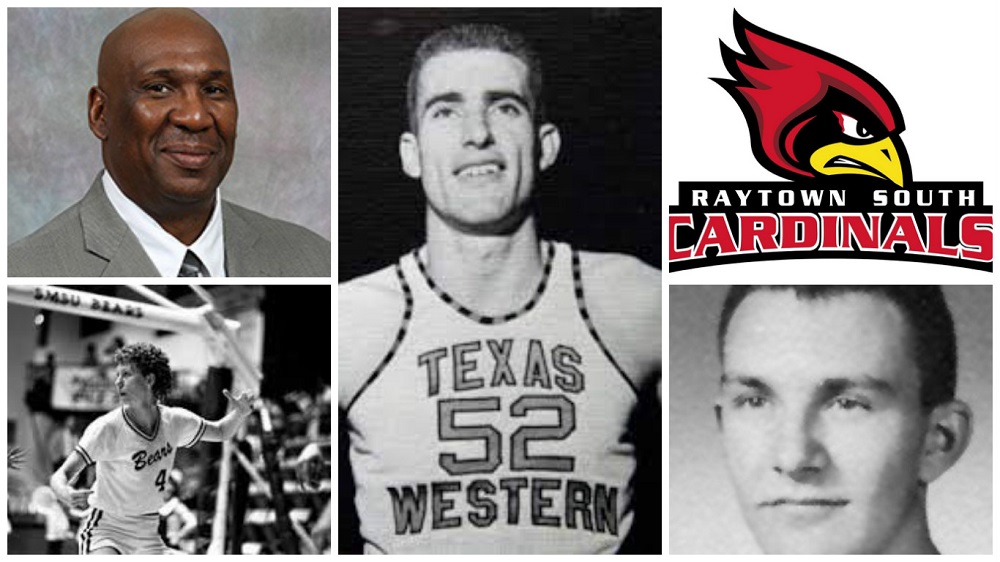

Inductees

Jerry Armstrong

September 24, 1944—February 4, 2021

To Jerry Armstrong, the cause was bigger than one individual.

Decades after he was part of the 1966 Texas Western team that used the first all-black lineup to win an NCAA Tournament – Armstrong never got in the game that night — the Missouri native received an apology from coach Don Haskins.

“I said, ‘Well, Coach, you know I wanted to play. And I felt like I could play,’” Armstrong recalled. “And I said, ‘But (the movie) ‘Glory Road’ and helping blacks all over the southeast break the color barrier in college basketball, that was a good thing. I was glad to have been a part of that history.’”

Armstrong certainly made an impact in and beyond basketball, first as a standout at North Harrison High School and later as a longtime high school basketball coach in the Show-Me State. And for his lifetime of work, the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame proudly inducted Armstrong with the Class of 2016.

What a journey it has been.

Armstrong and his four brothers grew up on a farm near Eagleville, near the Iowa line. They hunted, fished and played sports like so many others. But he fell in love with basketball in the fifth grade, when he was asked to join the seventh-grade team.

“They needed extra players because it was such a small school,” said Armstrong, who eventually graduated with 28 others. “The principal was our coach, and he came up the stairs to our room and took me down to practice. There weren’t really any other kids upset with me, to be able to do that. But I loved every minute of it.”

Armstrong went on to play at nearby North Harrison High School, earning all-conference three years, all-district two years and All-State his senior year. A 6-foot-5 standout, he led North Harrison to the state championship game in 1962 before falling to Bradleyville, 59-49.

At the time, his coach, George Kling, encouraged Armstrong to be a factor at a small college. So Armstrong headed to El Paso.

It was a life-changing decision. In fact, when “Glory Road” was released in 2006, Armstrong made it a point to use his celebrity the right way, speaking to middle schoolers and high schoolers about the dangers of drugs, hanging with the right crowd and working with people from different backgrounds.

“At one place, the kids asked, ‘Are you rich?” Armstrong said with a laugh. “I said, ‘I’m not financially rich. But I’m rich because I had the chance to play and made a lot of friends here and all across the country.”

Texas Western certainly shaped his thinking.

There, he was a three-year letterwinner and played 24 games his senior season. In fact, many credit his defense for the team’s 85-78 win against Utah in the national semifinal. Armstrong held Jerry Chambers to only a few points in the second half after Chambers scored 24 before halftime.

But it was the journey along the way that shaped him. Teammates had grown up in poverty in Detroit, Chicago, Albuquerque and Houston. As a freshman, Armstrong remembers a trip to New Mexico in which a restaurant refused to serve the team’s black players, leading the Miners to head elsewhere as a group.

At the time, while the Supreme Court had desegregated schools in its 1954 Brown vs. Topeka Board of Education ruling, many college teams were still all-white.

“It was a great culture change, but one I really enjoyed,” Armstrong said of choosing Texas Western. “You don’t win a national championship with a team that doesn’t get along.”

Armstrong never forgot those lessons. That’s why he managed to coach 21 years and compile a 329-195 record in Missouri high schools – at Trenton, King City, Richmond and Mansfield — before retiring in 1996. His King City team reached the state semifinals in 1987 and finished third.

The secret to his success?

“You can’t treat all kids the same,” Armstrong said. “You’ve got to treat them individually and let them know why they stand where they stand.”

Armstrong still lives in Mountain Grove with his wife, Mary. His son, Kevin, is the athletic director at Marshfield, and his son, Brad, is the assistant superintendent at Lebanon.

And, yes, the influence of Texas Western remains. A few years ago, former Arkansas standout Charles Balentine stopped by.

“He thanked me and the team for what we did,” Armstrong said. “He said he may never have gotten the opportunity to play. So he told his story, and I told my story.”

What a story it was.